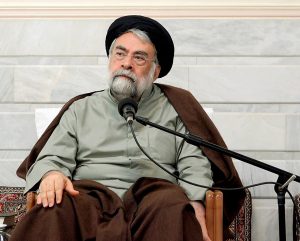

ARBA‘īN DAR FARHANG SHī‘A [ARBA‘īN IN SHIA CULTURE]. By Seyed Mohammad Mohsen Hosseini Tehrani. Qom, Iran: Maktab Wahy. 2020. Pp. 150. Paper. 750,000 IRR.

Each school of thought, in its content and identity, constitutes a combination of scientific and practical principles, as well as symbols that are referred to as the distinctive rituals and manifestations of that school. One of the significant rituals of the Shia school is the observance of Arba‘īn Hosseini.

Numerous works have been produced on this topic; however, this particular study distinguishes itself through a critical perspective provided by a Shia scholar regarding the practices surrounding Arba‘īn, specifically in relation to the burial customs for the deceased. This offers a fresh analytical lens.

The work consists of three chapters accompanied by an introduction. In the introduction, the author explores the linguistic and terminological meanings of the concept of ” shi‘ār” drawn from the lexicon of Al-Lisan al-Arab, where it refers in a literal sense to an article of clothing that clings to and is in close contact with the body. Furthermore, ” shi‘ār” can denote a war standard, an emblem raised by troops to identify their comrades amidst the fray. The author subsequently shifts focus to the fundamental tenets of Shia Islam, positing that the concepts of leadership (Wilayah) and Imamate represent the core essence and true banner of the Shia school of thought. The divergence between Shia and Sunni paradigms fundamentally revolves around the issue of Imamate and leadership. The Shia look to the infallible Imam not merely as a source of juristic rulings, but fundamentally as the mediator between the Creator and the creation, facilitating divine grace and representing the point of connection between humanity and God. The author critiques the cultural practice of holding commemorative gatherings on the seventh, fortieth, and anniversary days for the deceased, arguing that such practices deviate from traditional norms. He contends that the appropriate mourning period prescribed is three days and that commemorating Arba‘īn is specifically tied to Imam Hussein, a practice that has not been extended even to other infallible Imams.

The work consists of three chapters accompanied by an introduction. In the introduction, the author explores the linguistic and terminological meanings of the concept of ” shi‘ār” drawn from the lexicon of Al-Lisan al-Arab, where it refers in a literal sense to an article of clothing that clings to and is in close contact with the body. Furthermore, ” shi‘ār” can denote a war standard, an emblem raised by troops to identify their comrades amidst the fray. The author subsequently shifts focus to the fundamental tenets of Shia Islam, positing that the concepts of leadership (Wilayah) and Imamate represent the core essence and true banner of the Shia school of thought. The divergence between Shia and Sunni paradigms fundamentally revolves around the issue of Imamate and leadership. The Shia look to the infallible Imam not merely as a source of juristic rulings, but fundamentally as the mediator between the Creator and the creation, facilitating divine grace and representing the point of connection between humanity and God. The author critiques the cultural practice of holding commemorative gatherings on the seventh, fortieth, and anniversary days for the deceased, arguing that such practices deviate from traditional norms. He contends that the appropriate mourning period prescribed is three days and that commemorating Arba‘īn is specifically tied to Imam Hussein, a practice that has not been extended even to other infallible Imams.

In the first chapter, the author investigates the term ” Arba‘īn” within the Islamic cultural framework, noting its longstanding relevance across various nations and religious traditions. The significance of the number forty in Islamic teachings is highlighted—evidenced by narratives stating that God created human over a span of forty days, and the attainment of human maturity in intellect occurs after forty years of life, according to the Quran. Further eschatological notions indicate that a person’s prayers remain unaccepted for forty days if they consume alcohol or engage in backbiting against their fellow believers. The concept of neighborhood extends over a span of forty houses from all directions, underscoring the profound significance of the number forty within religious teachings, which state that an individual who performs sincere deeds solely for God over a period of forty days will experience the outpouring of divine wisdom.

In the second chapter, the author addresses the philosophy behind Imam Hussein’s uprising. The event of Imam Hussein’s martyrdom serves as the quintessential standard for discerning right from wrong across all levels of human progression in Shia culture. This historical episode, characterized by its unique attributes, represents an exceptional occurrence in human history, executed under the guidance of an infallible Imam. The author notes two predominant perspectives on the tragedy of ‘Āshūrā: the emotional interpretations of the general populace and the heroic narratives of certain intellectuals, though he emphasizes that the dimensions of Imam Hussein’s uprising extend beyond mere rebellion against tyranny, suggesting that viewing it through a limited lens, as the first perspective does, inadequately captures its essence. The unique attributes of the ‘Āshūrā incident, led by an infallible Imam whose every word and action exemplified divine qualities, highlight that the primary motivation for Imam Hussein’s struggle was the revival of forgotten Islamic commandments and regulations; the opposition to the Umayyad dynasty served as a precursor to achieving this aim. As Imam Hussein articulated in his will to Muhammad ibn Hanafiya prior to his departure from Medina, “I did not rise for amusement, corruption, or tyranny; I have risen to rectify the community of my grandfather, Muhammad. I seek to enjoin good and forbid wrongdoing, and to adhere to the path and tradition of my grandfather and my father, Alī ibn Abī Ṭalib.”

The third chapter delves into the significance of Arba‘īn within the Shia faith, highlighting it as a distinctive rite unique to Shia Islam— One of the distinctive Shia rituals is Arba‘īn, a practice that does not exist even for the Prophet of Islam and other infallibles. Islamic traditions affirm that the pilgrimage associated with Arba‘īn is one of the defining markers of Shia identity, reflecting the profound significance attributed to this communal religious observance, which annually attracts millions of Shia participants from around the globe to Karbala, Iraq. However, contemporary practices have unfortunately deviated from this intended observance, as adherents now commemorate Arba‘īn on behalf of their deceased, a custom that is inherently specific to Imam Hussein. Traditional Islamic practices, as delineated by the Prophet and the infallible Imams, permit only three days of mourning for the deceased, as evidenced by the mourning of Imam Hussein’s family upon their return to Medina, following the Prophet’s tradition. The concepts of “seven,” “forty,” and “year” regarding mourning are not recognized within Islamic doctrine, with memorial observances exclusively reserved for the infallible figures. The author suggests that permitting Arba‘īn gatherings for the general populace detracts from its significance as a distinctly Shia standard.

The third chapter delves into the significance of Arba‘īn within the Shia faith, highlighting it as a distinctive rite unique to Shia Islam— One of the distinctive Shia rituals is Arba‘īn, a practice that does not exist even for the Prophet of Islam and other infallibles. Islamic traditions affirm that the pilgrimage associated with Arba‘īn is one of the defining markers of Shia identity, reflecting the profound significance attributed to this communal religious observance, which annually attracts millions of Shia participants from around the globe to Karbala, Iraq. However, contemporary practices have unfortunately deviated from this intended observance, as adherents now commemorate Arba‘īn on behalf of their deceased, a custom that is inherently specific to Imam Hussein. Traditional Islamic practices, as delineated by the Prophet and the infallible Imams, permit only three days of mourning for the deceased, as evidenced by the mourning of Imam Hussein’s family upon their return to Medina, following the Prophet’s tradition. The concepts of “seven,” “forty,” and “year” regarding mourning are not recognized within Islamic doctrine, with memorial observances exclusively reserved for the infallible figures. The author suggests that permitting Arba‘īn gatherings for the general populace detracts from its significance as a distinctly Shia standard.

While the author provides a novel and critical perspective on the Shia community’s practices surrounding Arba‘īn for the deceased, it would be beneficial to incorporate a historical overview of the development and fluctuations of the Arba‘īn observance over the centuries and its relationship with the annual pilgrimage performed by Shia adherents. Questions such as whether the Arba‘īn pilgrimage as we observe it today has roots in the traditions of early Shia communities and the historical trajectory and development of this practice could merit a separate chapter titled “The Nature of the Arba‘īn Pilgrimage.”

Hossein Baqeri

Tolou International Institute